Electromagnetic compatibility has turned out to be a prerequisite in all industries that use electronics. The higher the digital complexity of products, which are increasingly smaller in size, the larger the risk of undesired interference. With communication modules and LED drivers to power supplies and industrial controllers, any device creating electrical switching can potentially cause noise on adjacent systems. Engineers use EMI test receivers, which are special equipment designed to identify, analyze and measure the level of electromagnetic disturbances to measure this noise and to establish whether a product complies with regulatory standards.

Even an inexperienced person in the sphere of EMC testing will be surprised at the sensitivity and accuracy of these devices. In comparison with general-purpose spectrum analyzers, the EMI receivers are designed with well-defined detector response regulations, bandwidth, and sequence of measurements defined by international compliance standards. This is why it is important to learn about the operation of EMI receivers any person, who works in the context of product development, compliance engineering or high-level troubleshooting.

All electronics gave electromagnetic emission of some amount. Power outages cause harmonics, digital circuits cause clock leakage, and motors cause transient bursts. These disturbances are measured with great accuracy using detectors like peak, quasi-peak and average detectors by EMI receivers. At times early learners tend to believe that the largest amplitude spike is the most significant, but regulatory testing measures noise based on special detector conditions. An example is, where very quick or isolated spikes are detected, quasi-peak detectors are favored over repetitive pulses since in real-world usage, repetitive energy provides more interference.

The inner layout of EMI receiver incorporates accuracy front end attenuation, pre-selection filter, mixers, low noise amplifiers and digital signal processing modules. These components collaborate to rejection of unwanted harmonics, eliminate overload by a strong signal, and have an accurate numerical result. This sort of instrument, e.g. those available through LISUN, would have pre-calibrated filter banks at CISPR bandwidth requirements (usually 9 kHz, 120 kHz, or 1 MHz, depending on frequency range). These fixed bandwidths guarantee measurements to be consistent with world standards of EMC in preference to arbitrary analyzer settings.

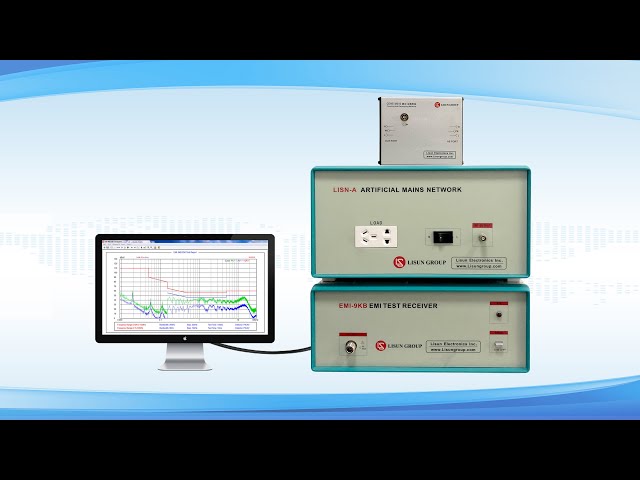

One large use of EMI receivers is in the conducted emission test in which noise propagating along power lines is monitored. Radiated emissions become widespread in the air whereas conducted noise travels down the cables and into the grid or other surrounding devices. The engineers use a Line Impedance Stabilization Network (LISN) to connect the device under test to measure its conducted emissions. The LISN achieves a controlled impedance, transforming the noise in the conduction to the measurable voltage and isolating the undesired external interference.

One large use of EMI receivers is in the conducted emission test in which noise propagating along power lines is monitored. Radiated emissions become widespread in the air whereas conducted noise travels down the cables and into the grid or other surrounding devices. The engineers use a Line Impedance Stabilization Network (LISN) to connect the device under test to measure its conducted emissions. The LISN achieves a controlled impedance, transforming the noise in the conduction to the measurable voltage and isolating the undesired external interference.

Whereas spectrum analyzers and EMI receivers may seem similar their behavior on compliance conditions is radically different. Special detectors (quasi-peak, RMS-average and CISPR-average) are used in EMI receivers, but spectrum analyzers are unable to reproduce reliably. Time-domain scanning techniques are also available in EMI receivers which can enable them to measure noise changing rapidly.

The other significant difference is in the dynamic range processing. To prevent the distortion of the measurement path by large signals of out-of-band signals, EMI receivers provide overload protection and pre-selection filters. High frequency bursts may be misinterpreted as low frequency artifacts in a spectrum analyzer that has not been correctly pre-selected. For EMI receivers the measurements are maintained by rejecting these undesired signals automatically.

A novice will hear words such as peak detector or quasi-peak detector without knowing what they are alluding to. Peak detector only gives the maximum amplitude, irrespective of pulse repetition. The quasi-peak detector on the other hand discharges and charges based on a set time constant. It reacts more slowly to infrequent pulses and more quickly to interference repeating at a high rate. This is used to model the interference to AM radio communication, on which many current EMC standards have their roots.

As an example, a device that generates 80 dBμV peeps at irregular intervals can have quasi-peak limits (with slow repetitions). The same machine making less strong pulses that repeat quickly will break upon the repetition being punished by detectors that are quasi- peaked. The only instruments that can measure these particular relationships are the EMI receivers.

EMI measurements must be required with great accuracy. Thermal drift, aging and receiver component tolerance variations may occur in receiver response particularly in the wide frequency ranges necessary to be compliant. E Mi receivers are highly calibrated, with tests of linearity, frequency tests and reference comparison.

Laboratories in the ready professional have traceable calibration sources whose output has known characteristics. A standard calibration will involve checking detector response, checking detector measurement bandwidth and checking stability of noise floor. Most present-day receivers, such as LISUN units, have inbuilt self-diagnosis capability, which includes internal oscillators and internal reference circuits and compares both to a set of internal standards to ensure long-term stability.

Measurement sensitivity defines the ability of a receiver to be sensitive to low-level interference which still can result in regulatory problems. The smallest signal that can be detected is the noise floor. Receivers of EMI attain very low noise levels by shielded enclosures, temperature constant amplifiers and filtering stages which are optimally designed.

A novice might not understand that being more sensitive to the receiver is not necessarily good. Excess gain leads to noise within the system or overloads in the case of strong signals. Thus, the EMI receivers enable the attenuation to be controlled to maximize the dynamic range per test set-up.

EMI receivers are mandatory to achieve compliance certification but they are also important in the course of developing the product. To find the problematic frequencies early in the design cycle engineers frequently conduct pre-compliance scans prior to engaging in the expensive formal testing. EMI receivers assist in establishing root causes by displaying frequency patterns of switching regulators, clock edges or motor drivers.

Once noise sources have been identified, designers alter PCB layout, shielding, grounding technique or filter networks. The measurement of conduct emission test by EMI receivers hence falls under iteration improvement in design. EMI is much easier to rectify during an early prototyping than after the final design.

The first EMI receiver needed time-consuming manual tuning and reception. Nowadays, workflows are being simplified with the help of modern digital receivers. Time-domain scanning also enhances the speed of the measurement process and now much longer compliance bands can be measured in seconds instead of minutes.

Graphical displays compute limit curves and indicate the areas of failure and give statistical summaries. Peak, quasi-peak and average detector curves can be compared at the same time by engineers. Guided software workflows have an easy time integrating with LISNs, transient limiters, and pre-selection modules.

New users enjoy automated sequences of measurement steps that take them through the process of validation of setup, cable verification, ground verifications as well as the choice of limits. This eliminates the operator error that used to be a significant issue in the EMC labs.

EMI test receivers are a fundamental concept one cannot venture into the area of EMC compliance or electronic design without having a basic knowledge of them. These tools are much more than signal measuring devices they impose standardized bandwidths, detector responses and dynamic range requirements which represent real world regulatory test conditions. They provide their accuracy to make the conducted emission test meaningful, troubleshooting of products, and long-term design enhancement possible.

Using sophisticated digital architectures, dependable front-end filtering, and standardized detector operation, EMI receivers continue to be the key element in the electromagnetic compatibility engineering. LISUN provides strong and calibrated systems that allow both novice and advanced engineers to create accurate and repeatable measurements. This is by learning how to achieve control of EMI receiver behavior whereby the designers can avoid interference problems, gain compliance easily and develop products that reliably operate in a more congested electromagnetic world.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *